Introduction

By following a long-only investment approach, traditional investment funds can only benefit from rising stock prices. A new generation of funds, popularly known as 130/30 funds, aims to achieve superior returns by having the additional flexibility of selling short unattractive stocks, which enables them to turn falling share prices into additional positive returns. In order to ensure that the net exposure towards the market remains equal to 100%, the long exposure is also enlarged, resulting in, for example, 130% long combined with 30% short, hence the name ‘130/30’ (or, similarly, 120/20 in case of 20% additional longs and shorts). These funds are also known as ‘shortextension’, ‘alpha-extension’ or ‘enhanced active’ funds, but for the sake of simplicity we will refer to them as 130/30 funds in this article.

By following a long-only investment approach, traditional investment funds can only benefit from rising stock prices. A new generation of funds, popularly known as 130/30 funds, aims to achieve superior returns by having the additional flexibility of selling short unattractive stocks, which enables them to turn falling share prices into additional positive returns. In order to ensure that the net exposure towards the market remains equal to 100%, the long exposure is also enlarged, resulting in, for example, 130% long combined with 30% short, hence the name ‘130/30’ (or, similarly, 120/20 in case of 20% additional longs and shorts). These funds are also known as ‘shortextension’, ‘alpha-extension’ or ‘enhanced active’ funds, but for the sake of simplicity we will refer to them as 130/30 funds in this article.

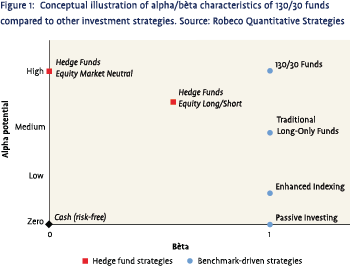

The 130/30 approach is a relatively new phenomenon. The key underlying idea of lifting the long-only constraint is not a revolutionary concept though, as taking short positions is a technique which hedge funds have been employing for many years already. The main difference with hedge funds is that the latter tend to focus on generating absolute returns, whereas 130/30 funds, similar to traditional funds, are benchmark driven. In fact, the whole point of a 130/30 structure is to create a framework which better enables portfolio managers to outperform their benchmarks, as we will explain in more detail in the following section. Thus, 130/30 funds are basically a hybrid investment product. On the one hand they provide the classic bèta exposure of a long-only fund (by having a net market exposure of 100%), while on the other hand they apply techniques for generating alpha that used to belong to the domain of hedge funds (the use of short positions). Figure 1 conceptually compares the alpha and bèta characteristics of 130/30 funds with those of other investment approaches.

Five years ago few people had heard of 130/30 investing, but by now many investors have become familiar with this new concept. Especially the sell-side has been actively promoting the approach, and the number of 130/30 products that are on the market has increased rapidly. On the buy-side, the largest pension fund in the world, CalPERS, is among the early adopters of 130/30 investing. In the Netherlands, the Blue Sky Group, which manages the assets of (a.o.) the KLM pension funds, has publicly announced its intention to switch a substantial part of its equity portfolio to a 130/30 approach. The popularity of 130/30 investing is also illustrated by the fact that even conferences are being organized which are entirely dedicated to this subject.

Five years ago few people had heard of 130/30 investing, but by now many investors have become familiar with this new concept. Especially the sell-side has been actively promoting the approach, and the number of 130/30 products that are on the market has increased rapidly. On the buy-side, the largest pension fund in the world, CalPERS, is among the early adopters of 130/30 investing. In the Netherlands, the Blue Sky Group, which manages the assets of (a.o.) the KLM pension funds, has publicly announced its intention to switch a substantial part of its equity portfolio to a 130/30 approach. The popularity of 130/30 investing is also illustrated by the fact that even conferences are being organized which are entirely dedicated to this subject.

In this article we examine if 130/30 investing is just the latest short-lived hype in the investment industry, or if it is an approach which is really here to stay. We first discuss the main theoretical pros and cons of a 130/30 approach. Next we describe some of the practical aspects of 130/30 funds. This is followed by a discussion of several recent new developments related to 130/30 investing. We end with conclusions and an evaluation of our findings.

The case for 130/30

Ever since Harry Markowitz introduced mean/variance portfolio optimization over fifty years ago, the long-only constraint has been known to have a large impact on optimal portfolio composition. More recently, Grinold and Kahn (2000) formally analyze the magnitude of the efficiency loss which active investors experience as a result of the long-only constraint, concluding that “the long-only constraint has enormous impact: it cuts information ratios for typical strategies in half!”. They also note that the long-only constraint is particularly problematic when an investor is facing a capitalization-weighted benchmark index, which is of course the case for most investors in practice. Clarke, de Silva and Thorley (2002) develop the generalized fundamental law of active management, which explicitly accounts for the impact of restrictions on the expected information ratio of a portfolio. They state that the information ratio (IR) of a portfolio is equal to the ability to implement raw return predictions (the transfer coefficient, or TC), times the correlation between predicted and expected returns (the information coefficient, or IC), times the square root of the number of independent securities to choose from (N):

IR = TC · IC · √N

Empirically, Clarke, de Silva and Thorley (2004) find that the greatest improvement in the transfer coefficient can be achieved by eliminating the long-only constraint. Removing this constraint is estimated to more than double the amount of information transfer.

Why does the traditional long-only constraint result in such a large drag on performance? Below we will discuss the three main ways in which a 130/30 approach is able to add value:

(i) Improved ability to implement negative views on stocks

(ii) Improved ability to implement positive views on stocks

(iii) Improved diversification possibilities

Ad (i): Improved ability to implement negative views on stocks

Ad (i): Improved ability to implement negative views on stocks

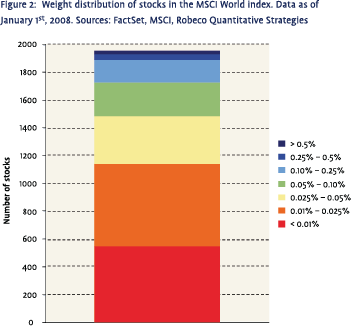

In order to outperform a benchmark, it is necessary to overweight certain stocks in comparison to their index weight, and to simultaneously underweight other stocks. However, placing the desired underweight positions is often a difficult matter, because the vast majority of stocks have a very small weight in the index. For example, about 1500 stocks out of a total of almost 2000 stocks in the MSCI World index have a weight of less than 0.05%, as illustrated in Figure 2. Fund managers are thus forced to place many underweight positions in second-best (or even worse) alternatives. Having the ability to go short is the obvious way to resolve this issue, because in that case the weight of a stock in the index no longer limits the amount by which it can be underweighted.

Assume, for example, that we expect the price of a certain stock to drop by 50% in the near future (ceteris paribus). If the stock has a weight in the index of 0.02% (the median weight of stocks the MSCI World index), then by not investing in this particular stock, a traditional fund manager can expect to realize an outperformance of 0.01% relative to the index, an amount which is clearly marginal. However, a 130/30 fund manager is able to underweight the same stock by, for example, 1%, by taking a short position of 0.98%. In this case the contribution of the position to expected outperformance is 0.5% and thus no longer negligible.

Ad (ii): Improved ability to implement positive views on stocks

Ad (ii): Improved ability to implement positive views on stocks

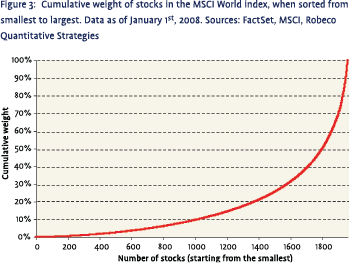

Every paper on 130/30 investing (an overview can be found in the references section) recognizes that the efficiency gains of these strategies are largely due to the fact that short positions allow a manager to much better exploit negative views, i.e. to benefit from stocks that are expected to underperform. However, there is also an additional effect involved, which is often ignored. If we again consider the MSCI World index, we can observe in Figure 3 that the combined weight of the smallest 1000 stocks in the index (‘small-caps’) is less than 10%, while the remaining fewer than 1000 stocks (‘large-caps’) account for the remaining over 90% of index weight. This implies that a long-only investor who wishes to create aggregate overweights and aggregate underweights of 60% each, will have to concentrate at least 50% of these underweights in large-caps, as the small-cap segment of the index simply provides less than 10% space. This distribution of the underweights is not only sub-optimal, but also has implications for the selection of overweights. If the largecap and small-cap segments of the market provide a comparable number of opportunities, the natural choice would be to distribute the overweights evenly over these two segments (i.e. 30% each). However, in that case the resulting portfolio will feature a large net overweight in small-caps at the expense of an underweight in large-caps, which introduces an unintended exposure to one of the most important systematic risk factors for equity portfolios. Clarke, de Silva and Thorley (2002) also mention this smallcap bias as an unintended but natural consequence of the long-only constraint. Alternatively, the investor may decide to enforce neutrality with regard to size segments. However, this implies that, similar to the underweights, at least 50% of the overweights need to be concentrated in large-caps and less than 10% of the overweights can be taken in small-caps. Thus, many potentially attractive overweight positions from the small-cap segment of the market must be foregone in this case. In short, the longonly constraint not only prevents an investor from placing many desired underweight positions, but also forces a manager to choose between two evils: exploiting all overweight opportunities, at the cost of ending up with a large net bias towards smallcaps, or remaining size neutral, at the cost of being forced to select overweight positions mainly from the large-cap segment of the market.

Ad (iii): Improved diversification possibilities

A 130/30 approach can improve upon a traditional long-only approach in yet another way. Consider a manager who expects one broad group of stocks to outperform another broad group of stocks, but who is unable to determine how the stocks within each of these groups will perform relative to each other. This is typically the case for quantitative managers, who have identified certain factors that they wish to be exposed to (e.g. value and momentum) in such a way that stock-specific risk is diversified away as much as possible. Such views can be implemented reasonably well in an enhanced indexing strategy, which is characterized by large numbers of small overand underweights. But if the aim is to reach higher tracking error levels, a fund manager is forced to take larger and more concentrated positions. Thus, long-only portfolios become increasingly exposed to stock-specific risk. For example, in case stocks are overweighted by 1% each, the maximum number of stocks in the portfolio is by definition limited to 100. A 130/30 investor, on the other hand, can use the extra space on the long and short side to attain higher tracking error levels whilst remaining well diversified. For example, for a typical quantitative global equity strategy we estimate that in order to realize a tracking error of 4%, a traditional portfolio should be concentrated in about 125 stocks, while a 130/30 strategy can take long positions in approximately 250 stocks and short positions in another 100 stocks and still reach the same tracking error level.

Arguments against 130/30

The arguments given in the previous section clearly show that 130/30 funds offer several fundamental advantages compared to long-only funds. However, 130/30 funds also have at least one important drawback, namely that their expenses tend to be higher than for comparable long-only funds. These higher expenses are the result of (i) costs involved with taking short positions, (ii) higher transaction costs due to the fact that more turnover is required to actively maintain the additional long and short positions, and (iii) management fees which are typically higher as well. Asset managers offering 130/30 funds argue that the improved potential for generating returns more than offsets this higher cost drag, as a result of which expected returns are higher on an after-cost basis as well. Although this may be true for certain individual managers, this logic obviously cannot be applied to the market as a whole, assuming that investing can be seen as a ‘zero-sum game’ before costs and a ‘negative-sum game’ after costs. Suppose for example that all investors were to adopt a 130/30 approach. In that case they would be worse off on average, simply as a consequence of the higher cost burden. Put differently, as a group, 130/30 managers can only deliver a positive net outperformance if this goes at the expense of another group of investors, who must be underperforming by an even larger amount.

Another concern is that the case for 130/30 might hinge critically on the assumptions that are implicitly used in the Grinold & Kahn (G&K) analysis framework. One important assumption used by G&K is that the objective of portfolio management is to maximize the information ratio, i.e. the ratio of outperformance to tracking error. But what if an investor does not care about tracking errors, e.g. because these can be diversified away to a large extent? In this case a Sharpe ratio maximization objective might be more appropriate. However, there is also a strong case for 130/30 from a Sharpe ratio perspective, because 130/30 strategies are associated with higher absolute returns at a roughly similar level of absolute risk (the latter observation will be addressed in more detail in the next section). A second important assumption in the G&K framework is that a portfolio manager is able to identify both highly attractive and highly unattractive stocks. In reality this is not necessarily true for many managers, e.g. traditional fundamental managers and concentrated bottomup managers. Without good quality negative views, the case for 130/30 largely breaks down and a classic long-only approach is in fact (close to) optimal.

Practical aspects

Managing a 130/30 fund is more challenging than managing a traditional long-only fund, because a 130/30 fund manager cannot just focus on identifying attractive stocks, but also needs to identify attractive short positions. This is particularly challenging for fundamental managers, as they will need to develop new skills and a different mind-set. For quantitative managers the step from long-only to 130/30 constitutes a much more natural transition however. Quantitative managers typically make use of forecasting models that identify both stocks that are expected to outperform and stocks that are expected to underperform, e.g. by means of ranking the entire universe of stocks from most to least attractive. As explained before, a portfolio manager is better able to implement these signals with a 130/30 approach than with a traditional long-only strategy. This likely explains why Johnson, Ericson and Srimurthy (2007) find that an estimated 60-80% of the 130/30 funds that are currently on the market follow a quantitative investment strategy. Quantitative managers do need to be aware though that relations are not necessarily linear. If a high score on a certain variable tends to be associated with outperformance, then it does not follow automatically that stocks with a low score on the same variable exhibit underperformance.

In theory the step from long-only to 130/30 is fairly straightforward, as a short position is simply a position for which the sign happens to be negative instead of positive. Actually making this transition in practice may involve quite a few hurdles however. For example, administrative systems need to be adjusted so that they can handle short positions, a relation with a prime broker who can facilitate the actual shorting needs to be established, lending fees for the short positions need to be monitored and the portfolio manager needs to be prepared for possible short squeezes or short positions that are recalled by the counterparty. Another important aspect is risk management. A long position which moves in the wrong direction automatically shrinks as a result. For example, in case of a return of -50% the position is halved. But the exposure to a short position which moves in the wrong direction actually increases in magnitude. In fact, while the maximum loss on a long position cannot exceed 100%, in case the stock price drops to zero, it is unbounded for a short position, as there is no maximum to the value that a stock price might reach. Thus, 130/30 funds clearly require a more sophisticated risk management process.

It is a common misconception that 130/30 funds by nature are more risky than long-only funds, simply because of the additional long and short positions. This misconception is also pointed out by Jacobs and Levy (2007). In fact, the absolute risk of a 130/30 fund tends to be similar to that of a long-only fund with a comparable tracking error, or even lower. To understand this, one should realize that both funds have a similar market risk, as both have a net market exposure of 100% (bèta 1). Assuming a similar tracking error, the deviation from the benchmark index is also comparable. In fact, as 130/30 funds tend to be more diversified than long-only funds with a similar tracking error, 130/30 funds may even exhibit a somewhat lower level of absolute risk. However, in terms of exposure to manager skill, 130/30 funds are undeniably riskier than their long-only counterparts, as the improved ability to implement positive and negative views acts like a double-edged sword. Investors in 130/30 funds are better able to capitalize on the skill of successful managers, but also bear the full brunt of the damage that can be done by value destroying managers.

In practice we observe different ways in which 130/30 funds are being constructed. In what could be called the integrated approach the long and the short part of a 130/30 portfolio are the result of one optimization process and one underlying strategy. The 130/30 approach is used to more efficiently implement this investment strategy than would be possible in a long-only portfolio. It is also common to take shortcuts however. For example, one alternative approach is to simply combine a 100% long-only strategy with a 30% allocation to a separate market neutral (100% long/100% short) strategy. The two strategies being combined in this way might even be entirely unrelated. In our view this is essentially a portable alpha approach. The main weakness of this approach is that it is suboptimal compared to the integrated approach, because a long/short portfolio which is optimal on a stand-alone basis will generally not be the optimal addition to a long-only portfolio with specific inefficiencies. Jacobs and Levy (2007) also argue that the portable alpha approach negates most of the efficiency gains that can be obtained with the integrated approach. From the marketing perspective of an asset manager the approach may be appealing though, especially in case the two component portfolios have already proven themselves in practice with good track-records. Another approach to 130/30 investing consists of simply scaling up the long positions of a traditional long-only portfolio from 100% to 130% and adding an optimized basket of shorts using for example a quantitative approach. This approach obviously also does not make full use of the potential which is being offered by 130/30 strategies. The same is true for an approach described by Gastineau (2008), who suggests to use sector ETFs for creating the short part of a 130/30 portfolio.

Several papers on 130/30 investing, e.g. Clarke, de Silva and Thorley (2004) and, more formally, Clarke, de Silva, Sapra and Thorley (2008), address the issue of the optimal amount of shorting. In other words, should a manager choose 130/30 or is perhaps 120/20 or 140/40 to be preferred? From a theoretical perspective, one of the key elements in this regard is the desired amount of tracking error. Whereas 110/10 might suffice for an enhanced indexing manager with a target tracking error of 1%, 170/70 could be the optimal choice for an aggressive high alpha strategy. Many providers appear to settle for 130/30 in practice, but this does not necessarily imply that all these funds are targeting medium-sized tracking errors. Simple marketing considerations may also be involved. Most investors are probably willing to accept a 130/30 fund as an alternative to a traditional long-only fund, but a 170/70 fund is more likely to be regarded as a hedge fund, which falls in a different asset category. In this regard we also note that there are decreasing marginal benefits to increasing the amount of leverage. In other words, switching from long-only to 130/30 yields much larger efficiency gains than the step of further leveraging up a 130/30 portfolio to 160/60.

Recent developments

Recent developments

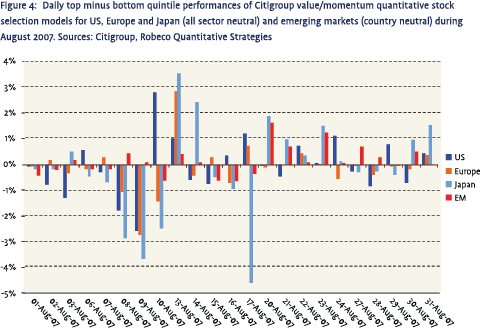

As the 130/30 concept originated in the United States, it is not surprising that the first 130/30 funds were U.S. equity funds. However, European, Asian and global 130/30 offerings quickly followed. The approach is now being applied to emerging markets as well, for example by Robeco and DWS. This is less straightforward, because emerging markets in general offer less possibilities for shorting individual stocks, and shorting costs tend to be higher as well. Robeco estimates that about 250-300 stocks in emerging markets can be shorted relatively easy and against acceptable costs, and concentrates on these specific opportunities for the short side of the portfolio. Despite the fact that these opportunities are concentrated in certain countries and among largecap stocks, a significant efficiency gain compared to a long-only approach is reported. Robeco advocates a quantitative approach, motivated by the good results found for quantitative stock selection models in emerging markets, as shown in for example Van der Hart, Slagter and van Dijk (2003). Interestingly, quantitative strategies for emerging markets appear to suffer much less from overcrowding than similar strategies for developed markets, as quantitative stock selection models for emerging markets proved immune to the turmoil which hit quantitative managers globally in August 2007 (as illustrated in Figure 4).

Another recent development is the introduction of 130/30 bond funds, for instance by Barings. A fund investing in corporate bonds, for example, may adopt a 130/30 approach by using credit default swaps for establishing additional long and short exposures. Although conceptually a 130/30 approach makes just as much sense for bond funds as for equity funds, it is important to keep in mind that traditional bond funds already make extensive use of derivatives in practice. For example, a bond fund might implement a view on money market rates by taking a 200% long position in 6-month money market futures combined with a 200% short position in 3-month money market futures (which is in fact not extreme in terms of impact on overall portfolio risk), as a result of which the fund would already have to be qualified as a 300/200 fund! Thus, in practice many traditional bond funds have already relaxed the long-only constraint, and bond funds which now embrace a formal 130/30 strategy may even turn out to be more restricted than their traditional counterparts.

A final recent development which we would like to mention is the concept of a 130/30 index, as described in Lo and Patel (2008). These authors develop a ‘representative’ quantitative stock selection strategy and apply a ‘representative’ portfolio construction process to create a mechanical 130/30 portfolio, which they argue can be used to gauge the performance of 130/30 managers. Although this is an interesting idea, we are rather skeptical towards their claims. In our view, one of the main characteristics of an index is that it is unambiguous and transparent. However, the stock selection strategy and portfolio construction process that are chosen by the authors reflect a large number of choices, each of which can have a significant impact on return. To name a few: which predictive variables are used for the stock selection model, how are the weights of these variables determined, which portfolio optimization algorithm is used and with which parameters, which turnover constraints are applied, etc. Thus, it is questionable if the proposed 130/30 index is indeed representative for the performance of quantitative 130/30 funds. Furthermore, the basic idea of creating an index which is representative for the performance of quantitative managers might just as well be applied in the long-only space. This suggest that the reason for linking the idea to 130/30 may be rather opportunistic – trying to benefit from the recent popularity of 130/30 in general.

Conclusion

Referring to the title of this article, we conclude that 130/30 investing is not likely to be a short-lived hype that will simply blow over, but an investment approach which is here to stay. The theoretical arguments in favor of a 130/30 approach are strong, and they are supported by empirical research. In fact, traditional long-only managers have more reason to be worried. Compared to 130/30 funds they have to, as it were, fight with one hand tied behind their back. After all, a 130/30 manager can do everything a longonly manager can do, and more. The main drawback of 130/30 funds is their higher total expense ratio. Thus, 130/30 investing is not a magical recipe for success. Only managers with true alpha-generating capability will be able to actually harvest the efficiency gains that are potentially available with a 130/30 approach.

On the practical side we observe several opportunistic approaches with regard to 130/30 investing. Various 130/30 equity funds basically try to take shortcuts, as a result of which they do no unlock the full potential which is offered by the 130/30 approach. We are also skeptical with regard to the recent emergence of 130/30 bond funds and 130/30 indices. A more promising recent development is the application of an integrated 130/30 approach to emerging markets equities.

Note

- Head of Quantitative Equity Research at Robeco Asset Management in the Netherlands. Email: d.c.blitz@ robeco.nl. Contact details: Robeco Asset Management, Coolsingel 120, NL-3011 AG Rotterdam, The Netherlands. The author thanks Laurens Swinkels and an anonymous referee for valuable comments on earlier versions of this article.

References

- Clarke, R., H. de Silva and S. Sapra (2004), Toward more information-efficient portfolios, Journal of Portfolio Management, Fall, p.54-63

- Clarke, R., H. de Silva, S. Sapra and S. Thorley (2008), Longshort extensions: how much is enough?, Financial Analysts’ Journal, January/February, p.16-30

- Clarke, R., H. de Silva and S. Thorley (2002), Portfolio constraints and the fundamental law of active management, Financial Analysts’ Journal, September/October, p.48-66

- Gastineau, G.L. (2008), The short side of 130/30 investing for the conservative portfolio manager, Journal of Portfolio Management, Winter, p.39-52

- Grinold, R.C. and R.N. Kahn (2000), The efficiency gains of long-short investing, Financial Analysts’ Journal, November/December, p.40-53

- Hart, J. van der, E. Slagter and D. van Dijk (2003), Stock selection strategies in emerging markets, Journal of Empirical Finance, 10, p.105-132

- Jacobs, B.I. and K.N. Levy (2006), Enhanced active equity strategies, Journal of Portfolio Management, Spring, p.45-55

- Jacobs, B.I. and K.N. Levy (2007), 20 myths about enhanced active 120-20 strategies, Financial Analysts’ Journal, July/ August, p.19-26

- Johnson, G., S. Ericson and V. Srimurthy (2007), An empirical analysis of 130/30 strategies, Journal of Alternative Investments, Fall, p.31-42

- Lo, A.W. and P.N. Patel (2008), 130/30: The new long-only, Journal of Portfolio Management, Winter, p.12-38

- Sorensen, E.H., R. Hua and E. Qian (2007), Aspects of constrained long-short equity portfolios, Journal of Portfolio Management, Winter, p.12-20

in VBA Journaal door David Blitz