Socially Responsible Investing (SRI) is becoming increasingly relevant to institutional investors. In this paper we will review the various approaches to SRI from the perspective of a multi-manager. We will focus on several important issues that need to be considered when creating an SRI portfolio using external managers, as we find that investors with SRI goals should pay particular attention to some specific risk characteristics. We conclude that a portfolio consisting of dedicated SRI managers will typically have a larger tracking error to the overall market and will become more concentrated in certain sectors and styles, but also offers a unique set of diversification opportunities.

Socially Responsible Investing (SRI) is becoming increasingly relevant to institutional investors. In this paper we will review the various approaches to SRI from the perspective of a multi-manager. We will focus on several important issues that need to be considered when creating an SRI portfolio using external managers, as we find that investors with SRI goals should pay particular attention to some specific risk characteristics. We conclude that a portfolio consisting of dedicated SRI managers will typically have a larger tracking error to the overall market and will become more concentrated in certain sectors and styles, but also offers a unique set of diversification opportunities.

Abstract

- The universe of SRI strategies can be classified into three main categories: screening, proactive and thematic. Screening fund managers have a profile similar to the overall market, typically avoiding a limited subset of stocks that do not meet minimal SRI criteria. Proactive fund managers do not just avoid the ‘bad’, but actively seek the ‘good’ as part of their stock selection process. Thematic managers, offer deep expertise on one or two specialist areas, such as alternative energy or water management.

- Constructing a portfolio of selected specialist SRI managers is an efficient way to implement SRI goals. Such a strategy can consist of a com-bination of more passive (screening) and active (proactive/thematic) managers, and can be tailored to the investor’s own SRI goals.

- SRI Investors who are mainly interested in overall equity market exposure can simply allocate to screening fund managers. Investors who have more profound SRI goals should allocate significantly to proactive and, especially, thematic fund managers. Their more specialised approach focuses on stock selection within specific sectors and themes. Although this may provide significant long-term performance potential as the global economy starts to bring itself onto a more sustainable footing, proactive portfolios tend to make major shifts from the overall equity market indices through concentrated risk exposures and clear style biases towards ‘small cap’ and growth stocks.

- These characteristics are clearly confirmed when performing analyses on some representative SRI managers and portfolios that we present in this article. One portfolio consists of screening funds, which is contrasted against a second portfolio that aims to maximise diversification, but is built up from proactive funds only. The first portfolio succeeds in having a high, style-neutral correlation to the general equity market. This stands in sharp contrast to the portfolio of much more active funds which fails to deliver market beta – but does succeed in providing uncorrelated alpha opportunities, quite similar to alternative investments.

- Within a portfolio context, the fundamental differences between screening strategies and proactive/thematic strategies provide a clear opportunity to profit from diversification benefits. This is what makes the multi-management approach very suitable to SRI strategies.

Types of Sustainable Investing

Even though there is no universally accepted definition of SRI investing, we can capture the essence through a definition provided by Eurosif1 : “Socially Responsible Investment combines investors’ financial objectives with their concerns about social, environmental, ethical and corporate governance issues”. We have grouped the many different ‘Sustainable Investment Strategies’ into three main categories:

- Screening: This is a relatively passive type of SRI, where any potential investments are filtered through a ‘screening’ process, scoring companies on several social, ethical and environmental criteria. The universe is usually a well known equity index and the criteria are mostly ‹negative›, meaning that a company will be excluded from investment if it scores poorly on one or more of the criteria used. Some screening managers combine this approach with a more active view, where those companies are selected that score best on certain positive criteria (the ‘Best in Class’ approach). Criteria can either be obtained externally from an independent SRI consultant or can be created in-house. ‘Screening’, in the end, is ratings-based and mainly concerned with creating an ethical portfolio by excluding certain stocks that do not comply with predefined ethical/social/environmental criteria. Therefore, the investment universe is constrained and creating alpha is not the main goal of the SRI overlay.

- Proactive: Proactive fund managers explicitly select companies that deliver a positive contribution to sustainable development. This can either be because such companies provide innovative solutions to environmental or social challenges, or because they have best-in-class management practices. The proactive approach is much less benchmarkdriven, and SRI research plays a more central role than it does for screening managers – thus requiring deeper in-house SRI research capabilities. Innovation is usually an important part of the selected companies’ strategies, which inevitably results in a clear small cap and growth style bias.

- Thematic: Thematic fund managers are by definition proactive, with the additional characteristics of concentrating on one or two very specific SRI subthemes. A typical example is Green Energy. In terms of portfolio composition, the style biases of proactive managers are even stronger in thematic managers, and the concentrated nature of the portfolios inevitably leads to higher volatilities. Thematic managers, however, tend to be deep specialists in their chosen industries, which tends to make their claims on alpha more credible.

Proactive and thematic fund managers are much more related to each other than to screening managers. Their strategies are more skill-based and they invest in companies with the explicit aim to benefit from opportunities that arise as a result of ethical, social or environmental trends. Creation of alpha is, therefore, the primary goal of their SRI research. In contrast, SRI ratings only serve to constrain the investment universe of screening managers.

Proactive and thematic fund managers are much more related to each other than to screening managers. Their strategies are more skill-based and they invest in companies with the explicit aim to benefit from opportunities that arise as a result of ethical, social or environmental trends. Creation of alpha is, therefore, the primary goal of their SRI research. In contrast, SRI ratings only serve to constrain the investment universe of screening managers.

The main difference between proactive and thematic fund managers is specialisation. Proactive fund managers are more diversified than thematic managers, and thus their proposition to investors is different: less alpha potential from specialisation, but a more mainstream profile due to greater diversification.

In addition to these three SRI categories, specialist methods of implementing a sustainable strategy exist as well. Examples of these are Community Investment, Social Venture Capital or Shareholder Advocacy. However, these fall outside of the domain of mainstream equity market products this article is focused on.

Implementing SRI through in-house management

For institutional investors, one obvious way to implement SRI ambitions is to build up their internal SRI expertise. Dedicated analysts can be assigned to manage the investments in-house, with stock selection incorporating ethical screening criteria. These criteria can be obtained from specialist sustainability advisors (such as SIRI Company or Oekom Research) or can be developed in-house. We argue that – quite similar to non-SRI portfolios – in-house development is more suited for beta-oriented screening strategies, but not for more proactive or thematic approaches, which require thorough specialist knowledge and resources. Costs and efforts will depend on the scale of implementation, but specialist knowledge is required and it generally takes time and money to establish this in the internal organisation.

Implementing SRI through multi-management

An alternative implementation route is the multimanager approach: building a portfolio of specialist SRI fund managers. This can consist of a combination of more passive (screening) and more active (proactive/thematic) managers, depending on the investor’s requirements. Although less in-house resources are required for a multi-manager approach, some specialist skills are still needed for manager selection, monitoring and portfolio construction. Costs are dependent on the manager’s strategy, where passive, screening based managers usually charge fees similar to traditional fund managers, while more active (and thus specialist/skills-based) managers generally charge higher fees. In the end, the advantages of the multi-manager approach are: ease of implementation, tactical flexibility (easy to adjust allocations to managers), cost control and the possibility to apply a best-of-breed specialists selection process. However, perhaps surprisingly, there has not been a lot of practical research done on the construction and monitoring of multi-manager SRI strategies. For that reason, we will focus the remainder of this article on this topic.

The challenges of SRI for a multi-manager

The first consideration for any SRI investor should be establishing the specific goal that is to be met. Perhaps an investor simply does not want to be invested in companies involved in child labour or weapons manufacturing, but has no further environmental considerations. This would only place certain specific restrictions on the investments to be selected, but does not necessarily result in a Sustainable Portfolio. We leave this aspect aside for now and consider an investor who pursues the broader definition of SRI. In that case, there are several issues that need to be addressed. These issues mainly relate to the differences in characteristics of the various types of strategy, and the goals to be met.

1. Formulating SRI targets and reporting on them

1. Formulating SRI targets and reporting on them

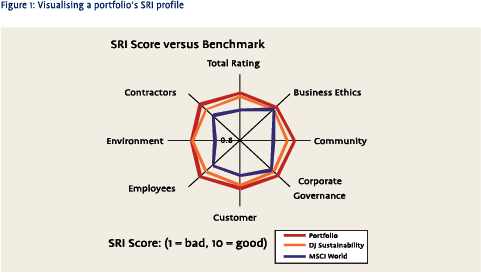

‘Sustainability’ is not a tangible property of a portfolio – as opposed to a portfolio’s P/E multiple or dividend yield. If clear SRI targets are to be defined, matching managers are to be selected, and their performance is then to be judged fairly over time, some sort of ‘sustainability’ metric needs to be developed. That metric should be easy to understand and be applicable across managers; it also needs to be objective (a manager should not judge his own ‘sustainability’). We believe that the stock-level ratings of external SRI consultants2 now cover a sufficiently large part of the investable universe to serve that role. In other words, a useful ‘sustainability metric’ can be derived from their research on the underlying stock universe from which all managers build their equity portfolios. One such SRI metric is shown in figure 1. For a number of different SRI dimensions, the average rating of stocks in the portfolio is contrasted against the average rating in the Dow Jones World Sustainability index and the conventional MSCI World index.

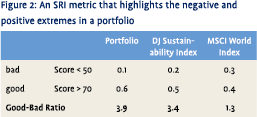

This type of visualisation lends itself well to evaluate either a single manager or a multi-manager strategy on the various dimensions of sustainability. However, averages do not reveal anything about the presence of extremes within a portfolio. A practical metric to highlight both the negative and positive SRI allocations in a portfolio is shown in figure 2:

The procedure is quite simple: it measures what proportion is invested in stocks with a rating below 50 (in the definition of the particular rating agency used here, that covers approximately the worst 30% of stocks) and what proportion is invested in stocks with unusually good SRI ratings. In practice, this ‘good-bad’ ratio has proven to be a good single metric to serve as a SRI target for portfolio construction and monitoring

2. Characteristic differences between screening and proactive managers

2. Characteristic differences between screening and proactive managers

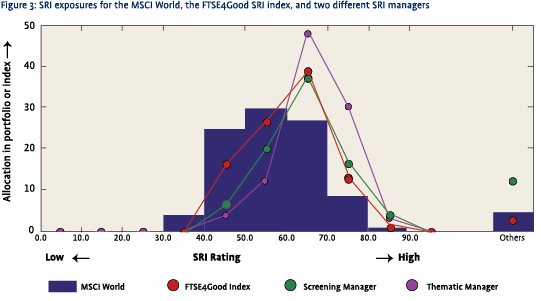

In figure 3, we would like to highlight some structural differences between two fund managers that we believe to be representative3 of each category: one fund manager from the peer group of Global Equity Screening and one from the peer group of SRI Thematic managers. As discussed before, screening fund managers typically follow a traditional equity benchmark quite closely, but improve the ‘sustainability’ of the portfolio only moderately. Proactive and thematic fund managers take a much more specialised approach, focusing on stock picking in specific SRI sectors and themes. Through that focus, they also have a much more significant impact on the ‘sustainability’ of the overall multi-manager portfolio. We illustrate this in figure 3, which shows how the two representative managers are exposed to stocks with poor (towards the left of the chart) and good (towards the right of the chart) SRI ratings.

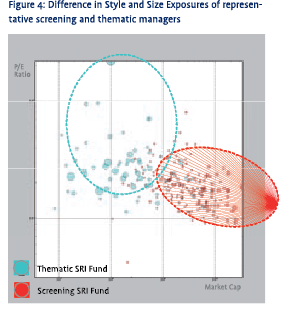

Screening and thematic managers differ in more than just the impact they have on the ‘sustainability’ of a multi-manager portfolio. They also have a clear influence on the style of a portfolio. Figure 4 illustrates this. Each bubble represents a position in a certain stock where the size of the bubble represents the size of the individual holding. On the horizontal axis, we plot Market Cap, on the vertical, P/E multiples as a proxy for the Value-Growth style dimension.

Screening and thematic managers differ in more than just the impact they have on the ‘sustainability’ of a multi-manager portfolio. They also have a clear influence on the style of a portfolio. Figure 4 illustrates this. Each bubble represents a position in a certain stock where the size of the bubble represents the size of the individual holding. On the horizontal axis, we plot Market Cap, on the vertical, P/E multiples as a proxy for the Value-Growth style dimension.

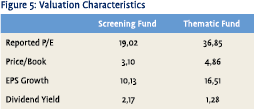

Figure 4 clearly illustrates the style differences between the two approaches. The thematic fund is more concentrated, with less and larger positions (as suggested by the bigger bubbles in the chart), while the screening fund is more diversified. The thematic fund is also more allocated to Growth stocks, illustrated by the higher P/E ratios. The screening fund is mostly allocated to large cap stocks, while the thematic fund has a clear small cap bias. Figure 5 shows some manager characteristics for the two SRI funds, again emphasising the differences in focus that we believe to be characteristic for the two approaches to SRI.

Figure 4 clearly illustrates the style differences between the two approaches. The thematic fund is more concentrated, with less and larger positions (as suggested by the bigger bubbles in the chart), while the screening fund is more diversified. The thematic fund is also more allocated to Growth stocks, illustrated by the higher P/E ratios. The screening fund is mostly allocated to large cap stocks, while the thematic fund has a clear small cap bias. Figure 5 shows some manager characteristics for the two SRI funds, again emphasising the differences in focus that we believe to be characteristic for the two approaches to SRI.

3. The role of screening and proactive/thematic managers in the portfolio

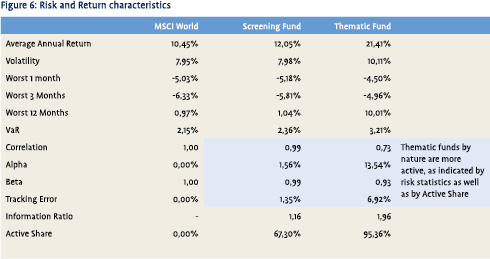

Figure 6 provides a summary of important fund manager characteristics. For comparison purposes, we have also included data for the MSCI World index. This table underpins another reflection on the strategic differences between the two categories of fund manager – their role in an investor’s overall investment portfolio.

Figure 6 provides a summary of important fund manager characteristics. For comparison purposes, we have also included data for the MSCI World index. This table underpins another reflection on the strategic differences between the two categories of fund manager – their role in an investor’s overall investment portfolio.

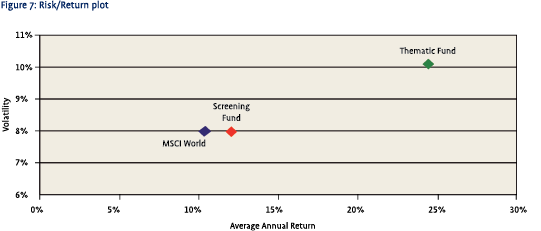

The screening fund closely follows the MSCI World index, in both risk and return characteristics. Correlation and beta are almost 1.0 and tracking error is very low at 1.35%. ‘Active Share’ is a measure for active management; it calculates the deviation from the index, based on differences in the weights of individual positions4. The 67.3% shows a certain amount of deviation from the index in terms of weights, but is not sufficiently high to label the fund as truly ‘active’. The thematic fund looks completely different. Although its performance may have been much higher than that of the index, its volatility, VaR and tracking error indicate that simply comparing returns against the index would be a case of ‘comparing apples to oranges’. Correlation to the index is much lower, indicating good diversification potential in combination with other index-tracking fund managers. Finally, the Active Share of more than 95% further emphasises the active nature of the fund. Figure 7 underlines the differences by plotting historical risk and return for the two funds in comparison to the MSCI World.

The various characteristics addressed above (portfolio concentration, style and size bias, risk and return statistics) are consistent with what can be expected from screening and thematic fund managers. The lack of commonality between the two approaches to SRI investing, clearly offers one big advantage: it allows for risk diversification when combining the two in portfolio construction.

The various characteristics addressed above (portfolio concentration, style and size bias, risk and return statistics) are consistent with what can be expected from screening and thematic fund managers. The lack of commonality between the two approaches to SRI investing, clearly offers one big advantage: it allows for risk diversification when combining the two in portfolio construction.

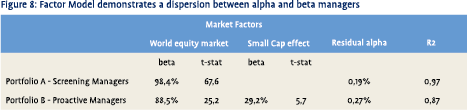

Another method to analyse the difference in behaviour of screening versus proactive/thematic fund managers is to look at the dependence of performance on various market factors. For this analysis, we have created two multi-manager portfolios, each consisting of 4 equally-weighted fund managers sampled from our research universe. Portfolio A contains screening managers, whilst Portfolio B contains proactive managers. The results are illustrated in figure 8.

The results show a clear and very significant relation of the Screening Portfolio to the global equity market. Given a Beta of 0.98 and R2 of 0.97, the portfolio mimics the character of the general equity market. The Alpha potential left for this portfolio after taking out the World Equity markets effect is only 0.19% (on an annual basis).

The same analysis performed on the Proactive Portfolio shows a much looser relationship with general equity markets (Beta 0.89, R2 of 0.84). This suggests a more active approach with other variables being important for the explanation of the return pattern. For this Proactive portfolio, there is another significant factor which could not be identified for the Screening portfolio: the Small Cap effect. Adding this to the model increases R2 to 0.87. This, again, is consistent with the Small Cap bias we illustrated before, using the analysis of a thematic fund manager’s holdings.

The same analysis performed on the Proactive Portfolio shows a much looser relationship with general equity markets (Beta 0.89, R2 of 0.84). This suggests a more active approach with other variables being important for the explanation of the return pattern. For this Proactive portfolio, there is another significant factor which could not be identified for the Screening portfolio: the Small Cap effect. Adding this to the model increases R2 to 0.87. This, again, is consistent with the Small Cap bias we illustrated before, using the analysis of a thematic fund manager’s holdings.

Conclusions

Portfolio construction is usually about finding a balance between long term returns and downside risks, where diversification opportunities are exploited to reduce risks where possible. Some academic research on SRI investing concludes that the impact of SRI on performance may be slightly negative in recent years, but could become significantly positive in the future as sustainability becomes an increasingly relevant economic factor. We believe that the impact of SRI on risk can be a significant negative if not dealt with properly. The problem of multi-manager portfolios being a stockpile of ‘black boxes’ to the investor becomes more apparent when SRI funds are involved. This stems from the characteristics that we have presented: a tendency to concentrate the portfolio’s exposure to particular sectors, to Small Caps in general, and to Growth-style stocks. The techniques that we have presented attempt to deal with this issue. Holdings-based analysis allows a multi-manager SRI portfolio to be monitored, and with minor extensions, it can be a useful tool in providing objective SRI metrics that help to establish practical goals and monitor implementation.

We also believe there is a benefit in combining screening fund managers in the core of a portfolio with allocations to proactive and thematic specialist fund managers acting as an active ‘satellite’ portfolio. The allocation to both categories should remain flexible; but generally, it would be recommended to invest at least half of the portfolio in screening fund managers in order to manage style risks.

From an overall risk/return perspective, thematic funds can actually help to diversify risk in the portfolio thanks to their lower correlation with equity markets in general. Returns in specialist areas such as renewable energy or water management are driven by important non-systematic factors (i.e., factors unrelated to the general market factors driving equity markets). Within the category of thematic fund managers, diversification is key as well. Having a large portion of the portfolio invested in just two themes (for instance, alternative energy and renewable technologies) can have a profound impact on the risk of the overall portfolio. Both sectors would suffer when energy prices decline. However, the range of specialist SRI themes that are ‘investable’ is growing rapidly, providing a much larger opportunity to create a well-diversified, SRI proactive strategy

Notes

- ‘European Social Investment Forum’, www.eurosif.org

- For this article, stock ratings from SiRi Company were used.

- The field of SRI manager research is perhaps still too young to make generalising statements. However, we believe the two managers to be representative of the approximately 200 SRI managers we have analysed for this study.

- An Active Share of 0% would mean the Fund has exactly the same holdings as the index, an Active Share of 100% would mean no overlap with the index at all.

in VBA Journaal door Sven Smeets (r) and Annemiek Steinmetz (l)