“With enough tailwinds, even turkeys can fly” captures the sceptic’s opinion about emerging markets. Over the last couple of years Emerging Markets Debt (EMD) has performed very well and as a result attracted a lot of new investors. What about the future? Are emerging markets, after their run up, going to bust as they did before? Where are the opportunities in the long term? This article will describe the evolvements of the EMD asset class. We will dive into the changing fundamentals of emerging markets, the demand for EMD and issues one faces investing in EMD.

Historic debt profile

Historic debt profile

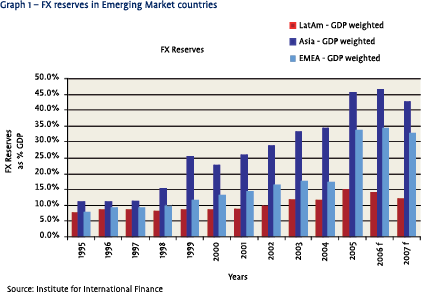

Before the 1990s Emerging Market Debt was a small part of bond markets, as primary issuance was limited, data quality was poor, markets were illiquid and crises were a regular occurrence. The market con sisted out of loans, that were mostly held by banks. Since the advent of the Brady Plan in the early 1990s, however, most of the defaulted loans were exchanged for tradable debt, inviting a more diverse audience of investors. The market continued to struggle with its reputation of being more prone to crises than other debt markets, as witnessed by the Tequila Crisis in 1994-95, the East Asian financial crisis in 1997, the Russian melt-down in 1998 and in this millennium the Argentine default in 2001. This reputation had a lot to do with the high visibility of individual issuers, as the most frequently used benchmark consisted only of about 13 countries in those days; this meant the market was dominated by more opportunistic players such as hedge funds, prop desks and High Yield (HY) cross-over investors. The universe was dominated by the Brady Bonds, as credibility of local debt issuance was very limited; talking about Emerging Market Debt meant talking about Hard Currency, generally in US-dollars and to a lesser extent in Euro and Yen. Due to its reputation of recurring crises, risk premiums needed to remain higher than justified by default risk and liquidity risk. Performance of the asset class needed to be strong to start convincing more conservative and more long-term oriented investors into the asset class. This was exactly what happened, how ever slowly. Countries took the management of fiscal and monetary policies more seriously, irrespective of the colour of the governments involved. The buildup of reserves, to serve as a buffer in leaner times, was a direct target for policymakers. It reflects broad balance of payment surpluses as well as an in creased ability to repay debt. It allowed policymakers to set domestic monetary, fiscal and debt policies more independently from the vagaries in international capital markets. This initially applied to the Asian countries after the Asian crisis, which converted to a mercantilist export-led growth to get the economies on safe ground, supported by extremely conservative fiscal and debt issuance policies. See graph 1 for the build-up of FX reserves that took place over the last 10 years. Policy discipline was initially dictated by markets and the IMF, but increasingly supported by an inherent conviction of policymakers, still prevalent until today. In a similar cycle, but slightly later, Russia adopted very tight policies after its embarrassing default, helped by a recovery of oil prices after 1999.

Central Europe followed in its footsteps, drawn into a European convergence path which was widely supported by the relevant voters, as it promised wealth and security, and a departure from anemic growth prevalent in communist times. Performance of the universe was heavily supported by these two re gions. Latin America continued to struggle to avoid the boom-bust cycles in those days. Importantly, however, after the Argentinean default, Brazil with stood similar pressure, despite its leftist candidate gaining power in 2003. Brazil adopted tight fiscal and monetary policies and increasingly gained credibility by the markets, as Mexico had already done before. FX-regimes were defined more realistically and flexibly. Given the size of these economies in the Latin American context, Mexico and Brazil provided much guidance for the region.

Central Europe followed in its footsteps, drawn into a European convergence path which was widely supported by the relevant voters, as it promised wealth and security, and a departure from anemic growth prevalent in communist times. Performance of the universe was heavily supported by these two re gions. Latin America continued to struggle to avoid the boom-bust cycles in those days. Importantly, however, after the Argentinean default, Brazil with stood similar pressure, despite its leftist candidate gaining power in 2003. Brazil adopted tight fiscal and monetary policies and increasingly gained credibility by the markets, as Mexico had already done before. FX-regimes were defined more realistically and flexibly. Given the size of these economies in the Latin American context, Mexico and Brazil provided much guidance for the region.

As these developments unfolded, risk premiums came off, making access to credit easier and growth started to increase, though Latin America remained disappointing on this front, at least late in the 1990s and early this decade. However, market friendly policies, export orientation fuelled by the globalization and the commodity price surge started to pay off, allowing countries to reduce external debt and increase creditworthiness.

The importance of commodities

Though commodity prices have contributed in a major way to growth in emerging markets and emerging countries can to some extent be seen as a proxy on being long commodities, the dependence on commodity prices has gradually been reduced over time. Though not applicable to all countries (most notably Venezuela!), this is due to diversification of the economies involved towards more domestic growth and related services-orientation; empirically, performance of the various fixed income instruments has started to correlate more closely with the international markets and the (international) business cycle, rather than commodity prices per se. This is due to the fact that the level of commodity prices has reached such heights that setbacks will not undermine its support for these economies but act as a transmission mechanism for the international business cycle. Indeed, it can be seen that at times, when oil prices spike, emerging market debt and equities perform poorly, due to risk aversion as the main underlying factor affecting the market. From another angle, one could also argue that the likely demand for construction, infrastructure and consumer durables in the likes of China and India are likely to keep the growth in demand for commodities elevated.

Credit ratings

Credit ratings

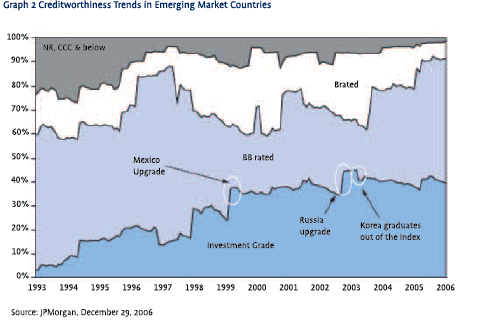

Despite the crises that continued in the 1990s, credit ratings across all rating buckets started to improve, as shown in graph 2. In 1993, almost no country in the index was investment grade; currently, the percentage of investment grade rated debt has increased to 40%, with limited risk remaining. Most of the countries that did not yet make it to investment grade, did also witness improvements of their creditworthiness. Some examples: Brazil having been close to default in 2003 might well make it to investment grade next year; Argentina, after its restructuring in 2005, continues to move up the ladder, from B- in 2005 to B+ in late 2006. Indonesia moved from default in 2002 to B+ in summer last year.

Across most countries, global liquidity has certainly been a helping factor, but this would not do justice to the efforts the majority of the countries put in to get their house in order. The rating agencies also try to develop their judgment independent of the stage of the cycle, supporting our case that structural improvements have indeed taken place.

When seen in this light, it should be no surprise that risk premiums came off and performance was very strong, as few countries defaulted. Essentially over the years, spreads remained wider than justified by its improving fundamentals; the credit rating agencies, having burnt their fingers in the Asian debt crisis, were slow in acknowledging the improving creditworthiness for most countries. Many more investors became involved in the asset class, increasingly comfortable in allocating from fixed income portfolios on a tactical or strategic basis. This phenomenon was supported by the need of international investors to diversify away from equities while still securing excess returns over  risk-free governments. Indeed, Emerging Market Debt, despite its status as risky asset class, proved it was possible to continue to perform when equity markets tanked in the years 2001-2003.

risk-free governments. Indeed, Emerging Market Debt, despite its status as risky asset class, proved it was possible to continue to perform when equity markets tanked in the years 2001-2003.

In 2005, spreads for B and BB countries started to approach the High Yield equivalently rated corporates while trading through them in 2006. The excess premium started to get exhausted. Despite the much improved creditworthiness, current spread levels below 200 bp seem to discount very few risks. Obviously, this ties in with the general observation that credit markets have performed well generally. At current levels of spreads, comfort can still be drawn in the case of EMD from growth remaining buoyant and sustainably so, at a much higher rate than in the developed world. I.e. it is still an improving asset class, as opposed to the HY universe. It is also expressed by the “positive outlook”-status various countries have, with very few on “negative outlook”. Default risks are increasingly remote for the bulk of the countries, given the build-up of (excess) reserves. Furthermore, countries increasingly buy back their external debt. Brady Bonds have mostly been retired or exchanged; IMF debt in most cases is being repaid. Together with the continuing allocations to the asset class, this explains the move towards tighter spreads and the likelihood that they will remain so.

Where from here?

As stated, countries are issuing less and less instruments in the international markets. For 2007, we foresee about $40 bn in (liquid) gross issuance, which is easily consumed by redemptions and coupon payments by the same issuers. This means that the universe of (liquid) Hard Currency sovereign debt as represented by the Emerging Market Bond Index Global (EMBIG) does not grow, despite the occasional newcomers. Last year for example Iraqi debt was added to the index. As governments are not targeting the public debt to decrease to the same degree as they are repaying external debt, they are increasingly tapping the local markets in local currency, as represented by the Global Bond Index –Emerging

As stated, countries are issuing less and less instruments in the international markets. For 2007, we foresee about $40 bn in (liquid) gross issuance, which is easily consumed by redemptions and coupon payments by the same issuers. This means that the universe of (liquid) Hard Currency sovereign debt as represented by the Emerging Market Bond Index Global (EMBIG) does not grow, despite the occasional newcomers. Last year for example Iraqi debt was added to the index. As governments are not targeting the public debt to decrease to the same degree as they are repaying external debt, they are increasingly tapping the local markets in local currency, as represented by the Global Bond Index –Emerging  Markets Broad (GBI-EM Broad).

Markets Broad (GBI-EM Broad).

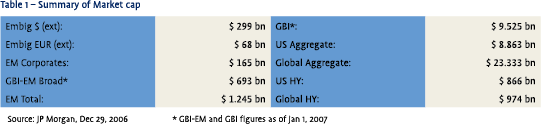

Another development concerns the strong growth of issuance amongst corporates in Emerging Markets. The improvement in business climate and the increasing stability of the countries concerned has allowed the emergence of this new type bonds to take hold, as represented by the “EM corporates index. See table 1 for outstanding capitalization of the various categories of tradable debt outstanding. GBI stands for the Global Bond Index (developed world), US Aggregate and Global aggregate are representing the (liquid) developed bond markets, and HY the US High Yield corporate “junk” bond market.

We see the emergence of local currency debt as a permanent phenomenon. The most important factors influencing the increasing importance of local currency debt can be stated as follows:

- status. To be known internationally as a creditor, rather than a debtor is a major motivation to repay external debt. This motivation is a powerful incentive in the case of Russia for example. As debt is also repaid to the IMF, this institution is forced to rethink its role. One of the options is to deepen its role as advisor to and coordinator of various governments, but its leverage is obviously more limited. The World Bank still has many projects in emerging markets, which are likely to continue; especially in those markets, where access to private sector credit is limited or unavailable.

- credit markets. Credit markets are acknowledged to perform an important part in economic development. While causation to GDP and vice versa remains in the realm of many debates, it is widely acknowledged that developed economies have strongly developed financial markets. Many emerging country policy makers therefore understand the need to develop a credit culture, to be able to handle risk in domestic corporate debt, mortgage debt and to allow for issuance of instruments outside the bank sector. Domestic government issuance will set a benchmark for these credit markets.

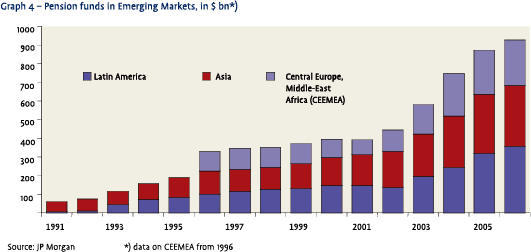

- local institutional demand. As part of the drive to reduce the countries’ vulnerability to shocks and to respond to longer-term finance gaps, many emerging markets have promoted the arrival of private sector pension funds and life assurance companies. These funds are growing strongly, as shown in graph 3 below. Given asset-liability matching issues and due to local regulation, the bulk of these funds need to be invested locally, preferably in long-duration instruments. We observe that these pools of funds are growing more quickly than the local public debt markets. In Chile and South Africa for example, the institutional portfolios are a multiple of the outstanding local currency denominated debt.

credibility. The fundamental developments as outlined above, have improved the credibility of policy making to a very high degree. Monetary policies are more independent, fiscal policies are well-behaved, reducing the risk that governments resort to printing money to finance irresponsible fiscal expenditures, leaving investors in local currency empty-handed.

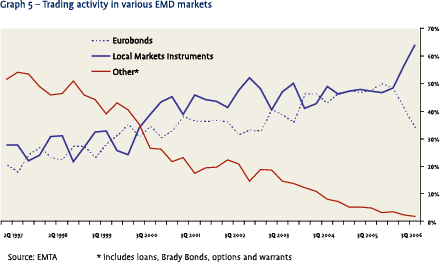

credibility. The fundamental developments as outlined above, have improved the credibility of policy making to a very high degree. Monetary policies are more independent, fiscal policies are well-behaved, reducing the risk that governments resort to printing money to finance irresponsible fiscal expenditures, leaving investors in local currency empty-handed.- search for yield and diversification by international investors. As international investors caused increasing correlation of the hard currency universe and spreads became less appealing, the more adventurous investors started to look for other opportunities that provided diversification and further performance. Since 2005, the local universe of government paper is being captured by the family of the GBI-EM indexes, measured by JP Morgan; the market capitalization is more than twice as large as the Hard Currency index, and growing. Trading activity has increased a lot the last years and local currency debt trading has surpassed Eurobond trading (representing Hard Currency debt). See graph 5.

Portfolio and risk management perspective

In the days that emerging markets represented a major risk in themselves, the prime source of risk was in spread risk. In other words, total return was dominated by the development of spreads over time; it also did not matter whether the bonds were floating or fixed, since that concept was only relevant for distinguishing between short and long term US-rates which was immaterial in the context of the high spreads. Due to a fairly homogeneous set of investors in the Brady and Eurobond markets, instruments tended to move in tandem within the hard currency universe. They nowadays still do move in tandem in most cases, but with the tight spreads and increasingly extended maturity and duration of most countries, the importance of US-Treasury risk has increased relatively. Apart from this generic interest rate risk, we distinguish three sources of risk: overall spread duration risk, country-specific risk and instrument-specific risk. The first refers to the market as a whole, which is driven by demand-supply considerations and comparison with other credit markets (most specifically High Yield corporates); the second refers to the individual country factors (mostly macro-economic and political risk), the third factor refers to the cash-flow and liquidity premiums embedded in the yield curves.

In the local currency markets, we have witnessed an increase in liquidity but also an increase in foreign participation. Previously, local currency markets could be approached almost solely from a bottomup perspective. Nowadays, top-down considerations have become more important, at least for short term reasons. In the longer term, local currency markets still behave as the specific fundamentals would suggest. The prime sources of risk in local currency markets can be shown to be FX (split between regional FX and country-specific FX risk) as well as local duration risk. Some markets move quite closely with the underlying developed markets, but correlations are not that high, especially if seen over a longer time horizon. So top-down considerations have always played a large role in HC and are increasing in importance in the LC universe. At the same time, diversification and yield enhancement opportunities still exist in both cases. As of the start of the year, only about $27 bn of international money had been benchmarked against local currency government debt, the rest is opportunistic; in hard currency, this figure is about $175 bn in dedicated investments. The situation for Local Currency debt now very much resembles the situation in the early 1990s when hard currency debt lacked a similar level of sponsorship by international investors. Sponsorship of local investors though, as referred to before, has increased in significance. We are seeing that increasingly, investors look at Hard Currency and Local Currency opportunities jointly, as the risks become increasingly intertwined.

Outlook

We believe the catch up of emerging countries to the developed world remains a powerful theme for the foreseeable future. Productivity is rising faster, the labour force in most countries is growing faster and the globalization provides a very comforting background to suggest that these countries can increasing ly exploit their potential. Obviously, the commodity cycle, high global liquidity and lower interest rates in the developed world have contributed strongly for providing tail-winds for an important subset of emerging countries. Some countries have not used the favorable global backdrop to consolidate and enhance institution-building or to improve the rule of law and its enforcement. These countries are going to encounter problems sooner or later. But for the bulk of the countries, the vulnerability has been reduced in various ways, making the impact from a possible shock far more limited, reducing default risk significantly. FX-reserves and reserve funds have been built up in excess of what most risk scenarios would demand, having used fiscal- and balance of payment surpluses. Exchange rate regimes are mostly flexible, providing another buffer for shocks. Debt profiles have been reduced and extended in maturity and are less dependent upon international risk appetite as local markets have been developed. Inflationfighting credentials have been established in many cases. Though commodity dependence remains, most instruments have started to correlate more closely to the strength of the (international) business cycle. That in itself reduces the appeal from a diversification point of view, but the effect has certainly not been exhausted. Trend growth in EM countries will remain higher than the developed world for the foreseeable future. Until then, international investors can and will go further to allocate risk to these markets, enhancing their development and allowing global convergence to take place.

Notes

- R.J. Drijkoningen is Head of Multi Asset Group at ING Investment Management, formerly Global Head of Emerging Market Debt at the same institution

- M.P. van Harten is Product Specialist Fixed Income at ING Investment Management, providing marketing and sales services to the Global EMD team

in VBA Journaal door Rob Drijkoningen1 (l) and MartenPieter van Harten2 (r)